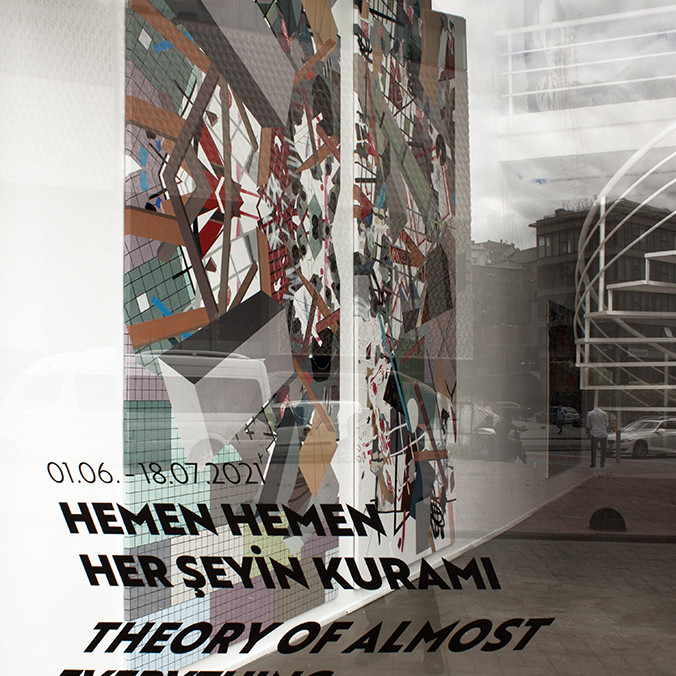

THEORY OF ALMOST EVERYTHING / EVLIYAGIL DOLAPDERE / 2021

Shadow Optics

No habrá nunca una puerta. Estás adentro

y el alcázar abarca el universo

y no tiene ni anverso ni reverso

ni externo muro ni secreto centro.

No esperes que el rigor de tu camino

que tercamente se bifurca en otro,

que tercamente se bifurca en otro,

tendrá fin. Es de hierro tu destino.

“Laberinto”, Jorge Luis Borges*

Placing yourself in front of a painting by Volkan Diyaroglu is a bold undertaking. The actual decision to look at his work, and to adopt a stance toward it, is in itself a chimera. One might perhaps describe any attempt to go to meet it as an illusory rapprochement. Or even, when the gaze puts up a resistance, we could speak of how the fabulous monster—lion’s head, goat’s body and dragon’s tail—overpowers the spectator. Volkan Diyaroglu’s works demand a willingness that could snap on the first viewing if one does not truly look, because the artist exacts a committed gaze, one that does nothing if not challenge the eye and all the places it leads to. After all, here, seeing goes much beyond a simple opening and shutting of the eyes and entails an exploration into the depths of the gaze.

At a time like the present when images glide through our hands, more than our eyes, with barely a few seconds to register them; at a time when images no longer belong to us—because they leave no trace to follow, because they have no origin—there is no minimum time span to capture them and to let them rest, to make them talk or to remain silent. By reproducing themselves, images today abstract themselves from the present moment without prior notice, without any other image than the image of the image. As Martin Prada argues, in the face of this situation, art affords another time. This would be the time of the resistance of looking and not simply a question of seeing or not-seeing, like the “shadow optics” Hérnandez Navarro cites from Lippit.

Ever since art lost its hegemonic role in the construction of visual culture, artists have exposed the weakness of art as compared with the other mediums with which it has entered into competition. Having said that, by exposing this weakness and displacing its field of action to places which were not conventionally assigned to it, artists have managed to kept alive the drive to see; to see differently. Accepting this crisis in visuality, throughout the twentieth century artists had put forward alternative visions to the centrality of vision. It was no longer a case of art illustrating the value system dictated by power, nor showing a single way of seeing the world. Since the appearance of the avant-gardes and the reactivation of some of their tenets in the sixties and seventies, art has taken strength from weakness, acknowledging the exhaustion of the paradigm of modern art. It is the moment when art accepts that it has problems and that, in itself, it is a problem. This form of laying bare its condition is probably what has allowed it to resist and, somehow, to find its strength.

Faced with the avalanche of images that have bombarded our eyes since the sixties, and much more so today, preventing us from seeing anything, art offers other ways of seeing and also of showing what we do not see when our gaze is blinded. This is, to paraphrase Hérnandez Navarro, how art reveals the scotoma of vision, an illness that afflicts art, because otherwise art would show nothing but reality, a reality affected by “a crisis in the truth of the visible: an awareness that there are things we cannot see, and that the things we do see cannot be trusted.”

Right from the beginning of his practice in the early 2000s, Volkan Diyaroglu treated the canvas, and then other supports, as a testbed to experiment with the possibility of seeing, which he then followed with other concerns that ranged from politics to quantum physics and also the questioning of identity or the very conception of artmaking. This exhibition, The Theory of Almost Everything, showcases the recurring concerns in the artist’s work. Conceived as a kind of labyrinth, through which the spectator will have to gradually discover a series of clues in order to move forward along the exhibition walkthrough, this show is subtended by a sense of unease perfectly orchestrated by the artist. Chance also plays a big part in this walkthrough, although, as the artist reminds us, in line with the physicist and mathematician Pierre-Simon Laplace, «the mechanisms that govern particles are intrinsically random. We can discover the rules that govern this randomness and calculate the probabilities of each possible event happening.» This is the theory of everything, by which all known physical phenomena are interconnected and explained in one single theory and which Volkan Diyaroglu applies to everything that can be seen around us.

Bearing these considerations in mind, if we observe the evolution of his work, we could conclude that Volkan Diyaroglu is seeking to subject painting to speculative pressure. Somehow, his method has to do with responding to the need to capture everything, to draw those lines that, at a precise moment in time, could frame complexity, exploding it, breaking it down into many parts. Driven by an obsessive and conscientious quest for what governs everything, the artist makes use of whatever is at hand to put together the necessary formulas that would explain the unexplainable and grasp the ungraspable, so that, ultimately, the whole would be possible without neglecting its parts.

With the passing of time, Diyaroglu’s work takes shape as a compendium of concerns that, while apparently randomly found, are actually the end result of observation, its functioning and position in a given space, where everything seemingly takes place haphazardly. For this reason, at first sight his painting might appear to reflect the result of chaos that would foreclose the possibility of embracing it all in a simple glance, because this painting forces one to resist and, ultimately, to see the whole through its parts. As pointed out above, here, seeing is much more than an accelerated visioning or a complacent gaze. Volkan Diyaroglu applies himself to the canvas, as he also does in other processes and supports, weighing up the possibilities of interrelating things and their reactions. In this way, it is in the act of seeing further beyond that everything begins to take on meaning and to follow a certain logic, even though that logic is still an enigma.

Volkan Diyaroglu is not a physicist but an artist. And so he makes it possible to see or to understand what would otherwise seem improbable to see or to understand. This is because, at the end of the day, the picture, the painting, is a space of representation, an illusion if you will. His painting is not governed by deductive laws that subtend the nature of things, because the nature of art is deceptive and whimsical. It is true that we can find whimsy and deceit in the nature of things, which includes art; probably one of the optimum ways to show things as they are: as pure appearance. As we have argued, and as Volkan Diyaroglu intends, art reveals another way of seeing things and, in consequence, a different way of understanding them, not tied to deductive logic or to the demands of a fully-fledged demonstration.

It is worth pointing out that, for this exhibition, and so that nothing eludes his bag of tricks, Volkan Diyaroglu posits a walkthrough that forces the spectator to go back over his steps. In one way, Volkan Diyaroglu the magician turns this exhibition into a rhizomatic labyrinth replete with infinite ramifications which nonetheless contains a predetermined path that obeys the following formula:

1 ->2->3->6->4->6->7->6->5->8->10->11->6->9->6->14->6->12->13->6

It is underwritten by a carefully thought-out back and forth so that what arises fortuitously in a blind passage can be co-opted into a more participative journey. Volkan Diyaroglu is looking for an active spectator, accepting, like Duchamp, that each aesthetic experience assigns a constitutive role to the spectator. A spectator who, in the process of visualization, adds his own contribution to the creative act. And in order to enable this contribution and to ensure that nothing is lost along the way, over and above casual encounters, Volkan Diyaroglu seeks to maintain certain control over things and over the spectator. Therein the formulation of a magical equation that will guide the spectator in the Diyaroglunian labyrinth.

In El fin y el fin* (2015), a digital print in which a series of white particles float over a black ground, one could imagine a faraway constellation. And yet, what at first sight looks like a constellation vanishes when we draw closer and see something else. A key work in the exhibition, this piece forces the spectator to move in such a way that, when we see it again, the position and reading of the work appears to change, with both work and spectator subjected to an ongoing revision, to a state of mutation round which the rest of the works on exhibit revolve. It is both a point of departure and a point of arrival, understood as one and the same thing, like an uninterrupted circular motion.

To start with, three canvases mark the starting point of the exhibition, from which one is necessarily led to the image El fin y el fin. These works, with their unexpectedly contrived vertical format, somehow condense a large part of Volkan Diyaroglu’s experimentation over recent years. Objetos de la angustia. Todo es posible o imposible (2019), Las pantallas de la decadencia. Ángulos diferentes, momentos diferentes (2019) and Todo es casi simétrico o no* (2020) suggest, all at once, the possibility of an encounter with what the artist calls “the origin”. This would be the origin of the self, understood as subject, and its relationship with the object and perception.

As we have just said, these large canvases contain a large part of the elements that have been obsessively hovering over Volkan Diyaroglu’s work. The cubes and other square or triangular geometric figures and wefts are just part of the manifold forms that come together in the canvases. One could almost talk of theorems. And yet, here there is no proof of truth, however much it is sought after. Points, planes and space converge in the time and place of art. Because, as Magritte said, “Ceci n’est pas une pipe”. It is not reality we see in art, and not even an illustration of reality. We could however speak of reality in itself, connected with other multiple realities.

Like in the extraordinary Still life (2002) by Luc Tuymans, an artist with which Diyaroglu has very little to do, Volkan Diyaroglu’s paintings create misleading expectations, because in their work neither of these two artists illustrate reality. That is not the mission of art, which is to put reality into perspective and not to respond to facts in themselves. In any case, the facts will be conveyed to the spectator as a mystery or as a disruption; something unresolved in the artwork but which pose questions. Accordingly, what one ought to look at is not the theme as such but how it is treated. We could speak of vast expanses, of flawed acts, of impossible facts and lines that appear to cut across each other without touching. We could speak of time and of space, of emptiness and of air; we could speak of synthetic forms that question the act of looking, what we see or what we refuse to see and the power of images. Images that we do not see literally because they are figuratively a reflection of themselves, like incomplete registers of history. A history that engulfs the spectator like a Big Bang.

And with it, the spectator is given the responsibility of taking a stance. On which side do we stand? What are we looking at? Where are we headed? And from the place of paradoxical encounters, when everything seems to explode, ghostly apparitions are divested of their spectralness and reduced to concrete though not graspable forms, because Volkan Diyaroglu’s painting is rife with paradoxes and tropes that constantly warn us that appearances are deceptive. That would be the condition of all images, images from before, “images from before the digital era”, the artist seems to tell us; images that, by nature, are always seen in retrospect, because they were always the memory of an instant. And by doing so, by convoking these images, in conflict with those of today, the artist leads us to an area situated between reality and the representation of reality, one foreshadowed by Magritte’s pipe.

To a certain degree, Volkan Diyaroglu’s work partakes in a surrealist and metaphysical dimension. Which is why, similarly to Tuymans, from another place of painting Diyaroglu proposes ways out or possibilities in representation when, in fact, everything seems to be inevitably closed and obtuse. Therein the sane insanity of accepting the possibility of representation, the place of art from where to look and not see, to go beyond the appearances of the visible.

The above canvases are followed by another section of the exhibition called “Fear and Rejection” which includes three very different works: the canvas Antes, después y siempre (2019), the object called El abandono (2020) and the digital print Herramientas del hombre del siglo 21 para matar su tiempo* (2015). And while in the previous canvases Volkan Diyaroglu appeared to be possessed by the chimerical task of embracing everything and seeking the limits of the void—by dint of accumulation, conscientiously using all kinds of resources and techniques—here, in these works, it looks like he is following a process of involution. It is as if, somehow, he wished to halt everything and submit it to a process of revision. In doing so, he posits an engagement with specific events. He simplifies representations and offers greater clarity in the recognition of things and, yet, nonetheless, what we see is not simple to see.

On one hand, the canvas contains many signature elements of Volkan Diyaroglu’s work, like the frame, the window or the square within the square, over grids or trellises that reproduce countless squares on a vast formless grey ground. Gestures, geometries, blotches and straight lines, the broken and incomplete, the stable and mutable, are parts of a whole that is more clearly demarcated here. The clarity with which the canvas shows the painted elements is also mirrored in the digital print and in the object, almost as if they were works by some other Volkan Diyaroglu. In these works, as if they aspired to go beyond the formalism of Kosuth and a simple investigation into the nature of art, Volkan Diyaroglu falls back on the contingency of conceptual art in order to, not without irony, disclose the possible sides of the circumstance of being something probable; a mathematical calculation of the possibilities that a thing is fulfilled or takes place by chance. Here, the spectrum of possibility is added to the actuality of what it is, in such a way that, however cold his photographic formality or his minimal objecthood might seem, in this work we are speaking about a self that is constructed under laws that are no longer calculable, and not because they are uncontrollable.

And then, the section called “Proof, Action and Misunderstanding » presents a set of two canvases and an installation with digital prints. The canvases Lógica quemada (2019) and Estamos ahogados* (2019) are characteristic of the artist’s compositions: geometric configurations and wefts that break apart, insofar as they float in a permanently unstable space. Squares and cubes, straight lines and circles, dots and grids, among which the human figure sometimes makes an appearance, are part of the elements with which Volkan Diyaroglu submerges us in a labyrinth of shadows and mirrors. As an optical instrument, the mirror is much more than a visually attractive framing, becoming a dramatic formula that reflects the multiplicity of a self in ongoing construction. In these works, as in the previously mentioned canvases, the artist seems to be putting Gestalt theory to the test, taking as his own the axiom: “The whole is different to the sum of the parts.”

The need to organize and structure the whole, weighing up each and every one of the possible parts, could respond to an intention to explain that whatever we perceive is much more than the simple information picked up by our senses. Here is where Volkan Diyaroglu is open to chance, understanding chance and indeterminacy as a decided option for processes in which nothing is painted, written or said in stone. These methods—as evinced by the installation Un mundo de imposibilidades (2020) and the digital print Ascenso vano* (2020)—challenge conventional logic. A way of subverting the established order and of turning things on their head. Here there is a depersonalization of decisions, brought into play through dice. Not unlike Duchamp, it is more about setting in motion a device that calls into question retinal images, thus establishing a meta-reality in which one can indeed see other things. As the artist himself explains: “Here there are actions and misunderstandings. We play or we try to play with games we have invented in the belief that we are free. But the truth is that the game is rigged. Chance cannot pan out equally for everyone. We try to build a life in vain. And we drown in it.”

The final section of the exhibition, “Subject and Access”, contains the digital prints Nacer en el Medio Oriente (2015) and Selfie Ahogado (2017), as well as the video ¡Dar a luz! ¡Corta la leche!* (2017), creating a space which Volkan Diyaroglu has called “the bad-luck room”. This would be the place where the artist reveals his most personal side. Against black grounds we already saw in previous digital prints we can now see, on one hand, the artist’s profile covered by a transparent plastic. Selfie Ahogado is a self-portrait that, similar to the work With My Tongue in My Cheek, evinces, not without irony, what Herman Parret said about Duchamp: “The humour, or even the irony, cannot mask the agonistic status of the self-portrait.” Like a death mask, Volkan Diyaroglu produces a selfie which is not apt for Instagram. We are not dealing here with a happy-go-lucky or sympathetic self-portrait. The asphyxia with which the artist depicts himself is far from pleasing. Like Courbet and his self-portrait, Volkan Diyaroglu suffuses the scene with ironic despair, vacuum-packing it, as if the artist was preserving himself as material, as a commodity, against a materialist and scientificist conception of the world. Here we would be talking about a rapprochement to the being through an alchemical cataloguing of despair.

On the other hand, and coupled with this work, in the print Nacer en el Medio Oriente Volkan Diyaroglu persists with blackness: with shadow optics. In this work against a black ground, one can appreciate the transparency of a plastic that barely allows one to see an ace, the face of a die with one dot. This enigmatic image, that makes no bones about its surreal facet, is nothing if not a spectral portrait. A phantasmagorical vision in which a strange pregnant being figuratively emerges from the darkness, not yet ready to give birth. We could be talking about a foetal die, a die of embryonic, primitive, original chance.

Finally, ¡Dar a luz! ¡Corta la leche! puts things in their place. In this video, Volkan Diyaroglu shows scenes from his circumcision. Made from amateur home-videos taken during his sünnet, the artist presents the vicissitudes on which an identity that he resists is constructed; a reality in which he is forced to join and to take sides: we could speak of the sum of dice cast by chance, stringing together events and ultimately creating meaning in the void. With this video, and without losing sight of the opening work El fin y el fin, Volkan Diyaroglu squares the circle of this exhibition, the sum of its parts. Controlled chance, being born here and growing up there, being subject to impositions and the need to free oneself from them, all comprised in an apparent visual disorder in which the fragments that compose a whole are sectioned. “We do not decide where we are born” Volkan Diyaroglu contends, “or when we are born, in what culture we are born, etc. This creates a subject contaminated with a whole culture and with the social pressure of his surrounding environs. By pure chance we are born and live as a person contaminated or constructed by or against his environs. As Heidegger tells us, when we are born we are practically thrown into life. And from the beginning everything is born from random acts. You can take the reins of chance, but you can never fully control it. And you begin to play the game of life with the material you are given or which falls into your hands.”

José Luis Clemente

Valencia, March 2020